The much anticipated The Boy and The Heron is out, and I got a chance to watch it this past Sunday. The film is the first in ten years from Hayao Miyazaki since 2013’s The Wind Rises, causing many to wonder if it’ll be Miyazaki’s last.

Like Scorsese is to American cinema, Miyazaki is a master in the world of animation and anime, having worked in the industry since the 1960s. Miyazaki extensively incorporates Japanese landscapes and culture into his works, yet the humanistic themes in his films make them accessible and enjoyable for audiences worldwide.

Miyazaki enjoys exploring diverse narratives in his films and isn’t the type to create sequels. Nevertheless, specific recurring themes persist throughout his body of work. Environmentalism and humanity's connection with nature consistently emerge as central motifs in his storytelling, with some personal bits as well.

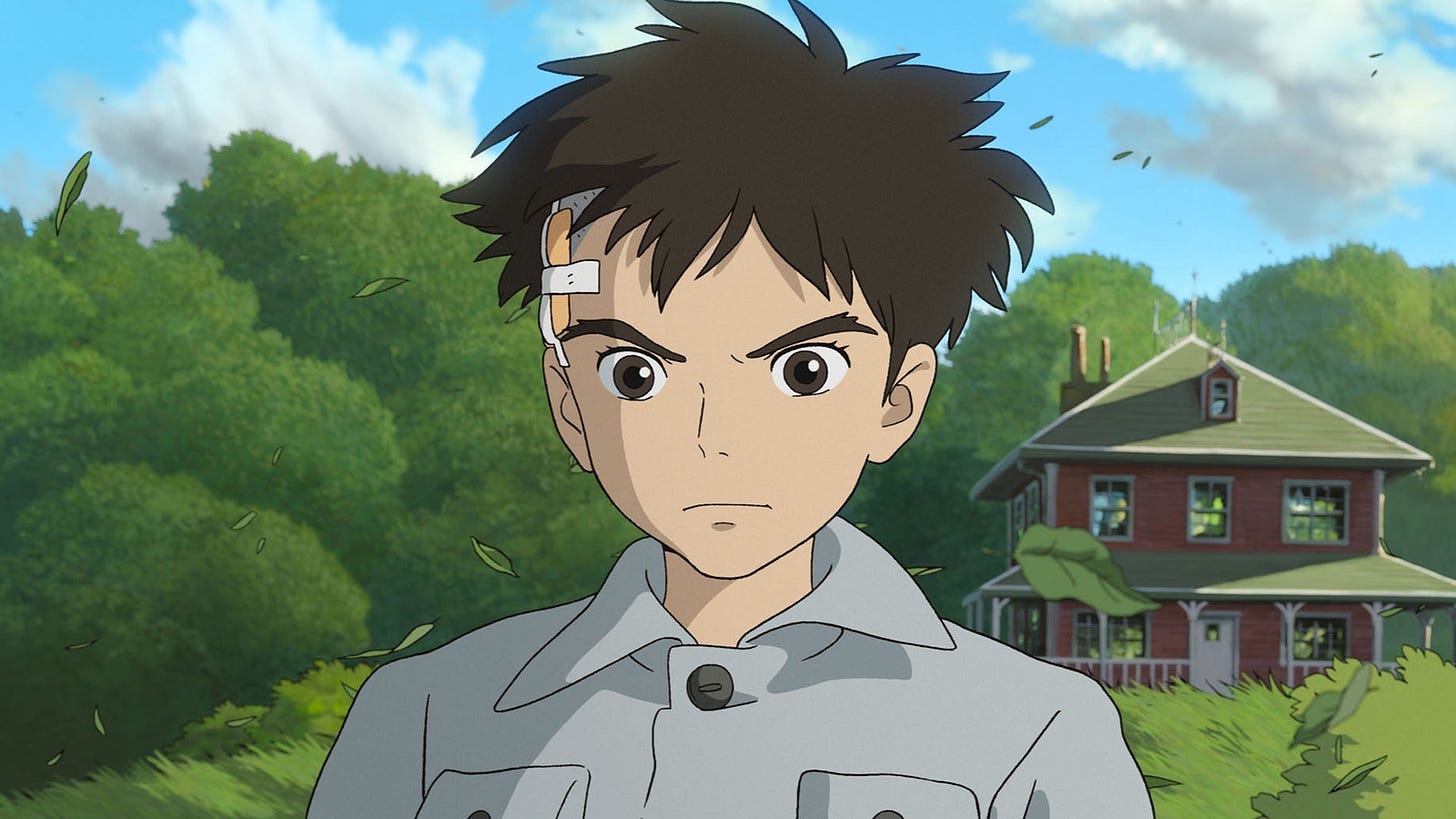

The Boy and The Heron revolves around Mahito Maki, a young boy who’s navigating the challenges of the Pacific War. Following his mother's passing in a hospital fire, Mahito stumbles upon an abandoned tower in his new town, leading him to uncover a mystical realm alongside a conversing grey heron.

It has a traditional Oz-fantasy land story, where a character explores mythical worlds in the search of something. Rather than overly explain these worlds to us, we’re propelled into the mystical and strange lands, creatures, and characters.

Personal Storytelling

The Boy and The Heron is arguably Miyazaki’s most personal film, having used personal stories for inspiration, with Mahito being crafted in the image of Miyazaki's childhood.

Mahito is troubled and grieving, doesn’t have many friends, and isn’t the kindest to most people. Mahito’s father, much like Miyazaki’s father, worked for a company involved in manufacturing fighter plane parts.

Miyazaki's family also underwent wartime evacuation from the city to the countryside, and the hospital fire depicted at the film's beginning reflects Miyazaki's memories of losing his mother.

Known for her strong convictions, Miyazaki's mother is a muse for several of the director's female characters, and Mahito's deep emotional bond with his mother mirrors Miyazaki's affection for his own.

The film feels like a written message to Miyazaki’s younger self, explaining what he should’ve done differently and as a way for the audience to view the mistakes and emotional state Mahito’s in. Much of the film centers on a world without conflict within your capabilities and how reflection is a key to moving on.

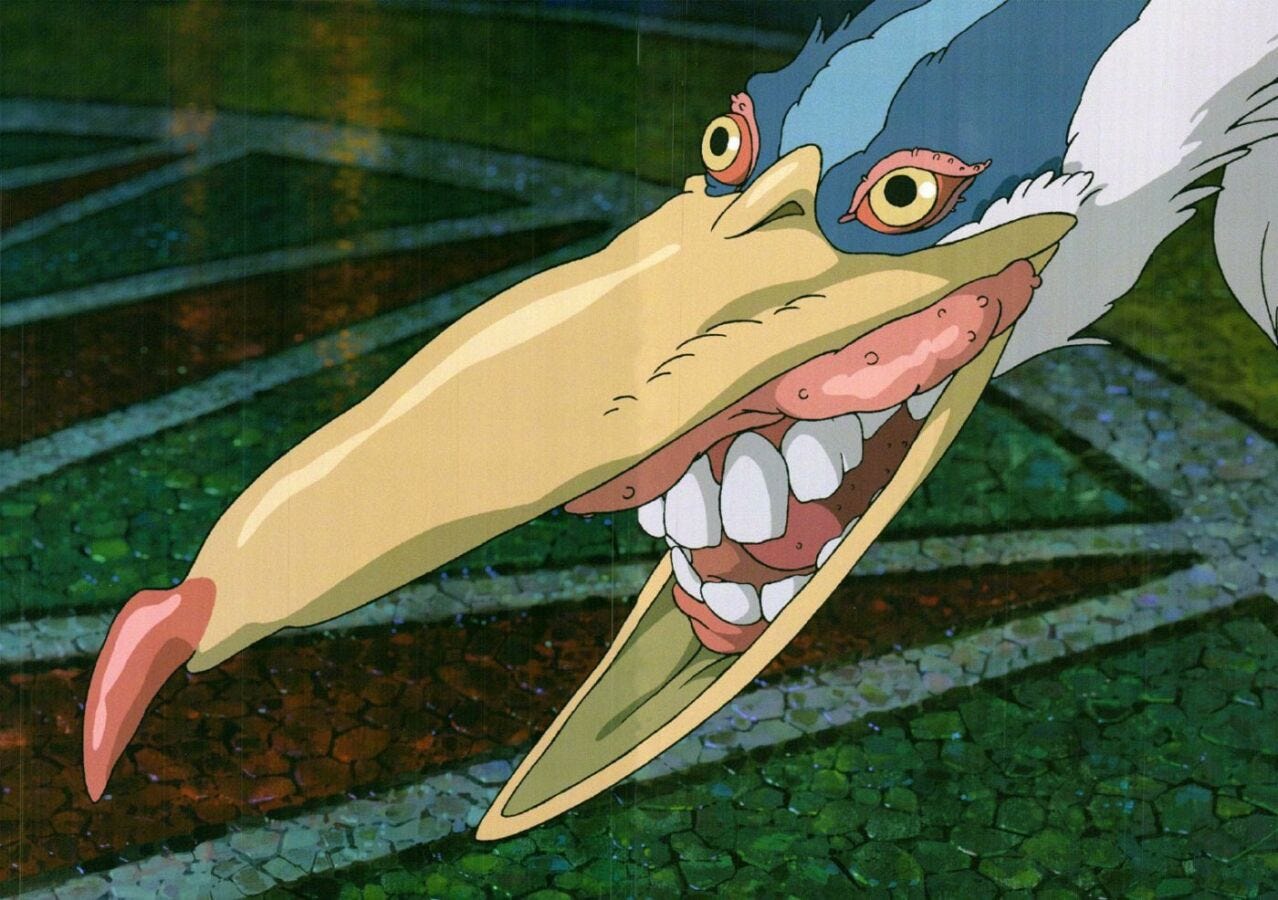

The Grey Heron

The grey heron maintains an air of mystery throughout the film. Distinct from the other creatures depicted, the bird exudes a palpable sense of power while being a paradoxical character.

The heron is both a deceiver who guides the protagonist toward the truth and a steadfast ally. Eventually, when the grey heron’s beak is damaged, he unveils his genuine identity–a diminutive, wise man who utilizes a heron’s skin for shape-shifting.

While you can attribute the grey heron to a folktale, I believe there’s a deeper meaning that’s connected closer to Miyazaki and the flaws we all have. Many of the beats blend as Mahito struggles to terms with his mother’s death, and his inner conflict connects to the grey heron, with the death of his mother being the end of his innocence.

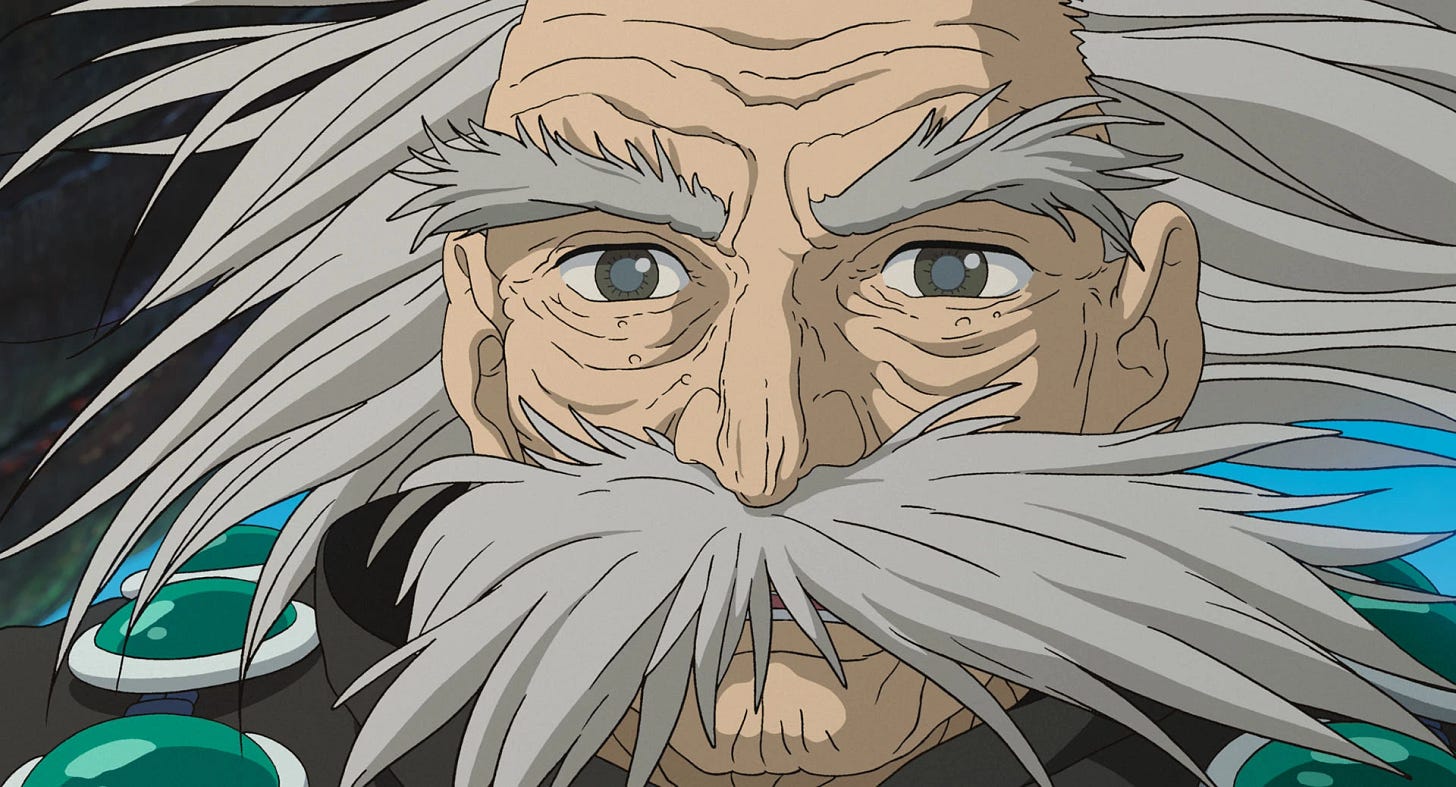

The Grand Uncle

The grey heron brings Mahito into a gateway that allows him to escape reality and exist in a fantasy world while searching for Natsuko, his father’s new wife, who’s gone missing. It’s a heartbreaking depiction of anyone dealing with the loss and subsequent impact of moving on or never getting over a heartbreak.

You can also draw a connection of loss—but rather mortality and time—with The Grand Uncle, a character who implores the pressing nature of responsibility and the fleeting passage of time. The character is a brilliant mind who withdrew into fantasy and forsaken his earthly connections to the imperfect reality driven by the desire to construct an idealized fantasy world.

From my perspective, the Grand Uncle symbolizes Miyazaki, and the fantastical realm within the tower mirrors his animation endeavors. As the film unfolds, the fantasy world's impending conclusion parallels Miyazaki's age, now in his 80s.

No one wants to age, no matter how optimistic you consider yourself. It’s odd being a species knowing how it all ends, and I imagine even someone as accomplished as Miyazaki has some regrets, whether they’re family or work-related.

Noble Pelican

One of my favorite scenes in the film is the Noble Pelican and the creature’s final words after being attacked for killing the Warawara. The Warawara are small bubble-like spirits that float up to be born in Mahito's world, and pelicans often attack them.

The dying pelican explains how they only kill the Warawara because they’re starving and have no other option for food. All they want to do is escape, but they’re trapped in this world without a solution in place other than to survive.

You can make two main points from the noble pelican and his final words: On the surface, it explains why people arrive at desperate measures in life without any upward mobility or help to guide them to a better path.

On a deeper level, Mahito's father building the parts of warplanes within the home and the procession of people carrying the rising sun flag are aspects of Mahito’s world that relate to the pelicans devouring the Warawara.

A pivotal moment occurs when Mahito expresses anger towards the noble pelican, only to realize later that the pelicans, much like himself, are victims of their challenging circumstances.

Final Thoughts

The Boy and The Heron mesmerized me and it’s remarkable how strong Miyazaki is as a filmmaker even with it being half a century since he started. While it’s not confirmed if The Boy and The Heron will be his last, it makes sense if true.

It has much to say about grief, regret, decision-making, time, and mortality–all influenced by Miyazaki’s current reflective state. To me, its central message is about perseverance and adapting to your environment while letting go of resentment and anger.

Mahito could’ve replaced The Grand Uncle and built a fantasy world without thinking about his life back home and his mother. Instead, he chose his world and the harshness that’s connected to it. It’s a captivating message about the gloominess of escapism and the need to live in the present.

Definitely see this in theatres.

"it’s remarkable how strong Miyazaki is as a filmmaker even with it being half a decade since he started." Believe that should be half a century...